Location D

The Japanese Canadians interned here during the Second World War, brought with them their skills, expertise and culture. Many were very successful business owners and craftsmen. The Matsumoto family were boat builders and their expertise was immediately employed to build the houses that they were all to live in. Schoolteachers began schools, Ministers created places of worship, green grocers such as the Kinoshitas found work in local stores. Stores began to stock many of the goods that were Japanese staples. Druggists, tailors, and forestry workers all found work as the sleepy community of less than 500 swelled to thousands.

A search of the New Canadian newspapers through the 1940s and 1950s shows “Seasons Greetings” from various businesses including Photocraft (Tak Toyota), Slocan Tailors (Kichiei Sakamoto and family), Murakami Sawmills (Mickey M. Murakami), and Slocan Soya Company (H. Matsubayashi and son) to name a few.

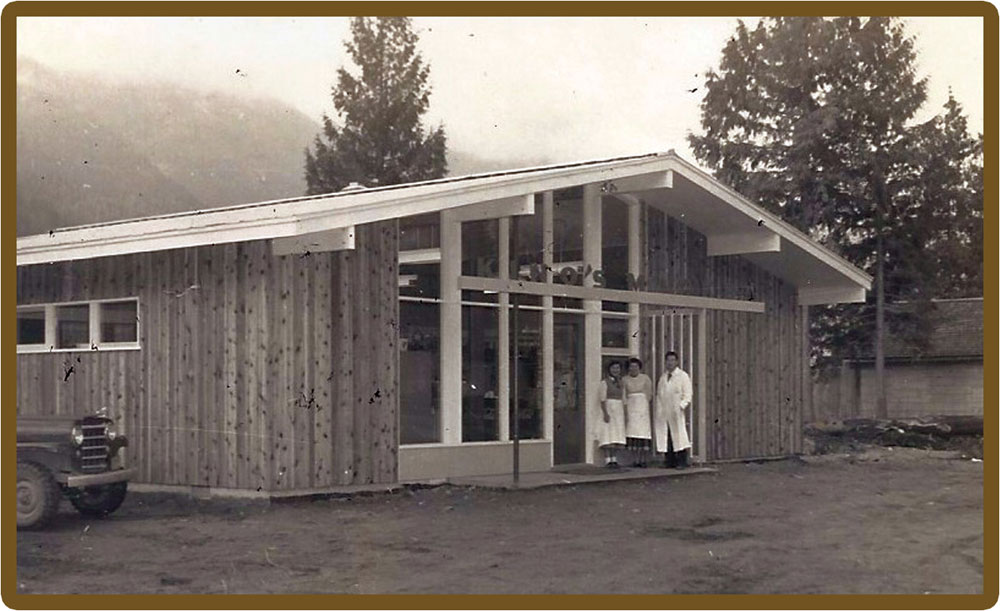

This panel highlights one of those businesses – Kino’s Market. We can still see today at the Slocan Village Market the original lines of the new store that James Kinoshita designed for their family market. It has been an important part of our community for more than half a century.

Diagonally opposite to this building to the south you can see another small building with murals that is currently not in use but was once the Village office. It was in this building that a small fire in a garbage can destroyed the town’s only record of cemetery burials. The building also served as the fire hall and, for a number of years after the fire hall had moved, local residents remember hearing the fire siren which was on a timer. It sounded every Sunday morning – more regularly than the church bells!

In later years, this building served the as the Women’s Institute base of operations. The BC Women’s Institutes have been a force for good works and community building since they were first organized in 1909, twelve years after the birth of the first Women’s Institute at Stoney Creek, Ontario. The founder, Adelaide Hoodless, saw the need for a meeting of country women to discuss common problems, and work together for their homes and their country. Their motto was fittingly chosen, “For Home and Country”. The Women’s Institute early became a vital part of each community. Fall Fairs and Flower shows were organized, lectures on subjects of interest were given, and classes in cooking and dressmaking were held. Social welfare, and the welcoming of new citizens was stressed. During the two World Wars, they were actively engaged in war work of all kinds, such as knitting for the Red Cross, canvassing for the Patriotic Fund, making jam for overseas, and helping the bombed out people of Britain with contributions of cash, clothing and wool filled quilts.

When the local chapter of the Women’s Institute moved into the building, they did extensive renovations. When this building was no longer habitable, the Women’s Institute moved down the block to share space in the Silvery Slocan Social Centre (also known as the Legion). The Women’s Institutes in BC were instrumental in improving the lives of the people in their communities and many things we take for granted today are due to the selfless actions of these groups. Things like: lines down the center of the road; the use of plastic bags on bread; and Children’s Hospital in Vancouver. Slocan was the last chapter of the Women’s Institute operating in the West Kootenay when it finally closed in 2015.

This Market – A Famous Architect’s Debut

Kino’s Market photos above courtesy of James Kinoshita, the architect/designer of the building while a teenage architecture student at U of Manitoba in 1952.

these market ads from The New Canadian newspaper date from the 1940’s and 1950’s.

The Internment Story

With legislation in 1942 under the War Measures Act government removed all “persons of Japanese race” from the Pacific Coast. Thousands of Japanese Canadians were sent to Slocan. At the railhead trainloads of displaced persons poured in, filling “ghost towns”. Slocan and its three instant satellite settlements of Popoff, Bay Farm, and Lemon Creek housed 4764 internees, 40% of the ghost town total. Total loss of rights, freedom and property was the big story for those who lived it.

Popoff Internment Camp

Popoff mushroomed quickly from vacant lands leased from Emilie and Konstantine Popoff in 1942. Two years later it housed near one thousand people with cabins, dormitories, mess halls, running water, gardens and a school. Store and dairy were managed with the assistance of the Kinoshita family, who had substantial grocery trade experience from their Vancouver years. Virtually nothing remains of Popoff, the first camp to be closed and demolished.

Young James Kinoshita & the Market

James was eight years old when his family was interned at Popoff. Youthful memories included fishing, hunting, matsutake mushrooms, swimming in the river, kendo classes, herding cows and picking cherries. Shortly after internment ended, his family bought the market business from Emilie Popoff, and moved it to Slocan City. Zenich and Yoshiko Kinoshita supplied food in the Valley for 32 years until their retirement in 1974. The “new” Kino’s market was designed by James as a student and was built from local woods and labour. The market was an extremely “modern” architectural treatment for the small town of Slocan. Its functional flexibility and Modernist design are still apparent today as the Slocan Village Market caters to changing community over half a century later.

James Kinoshita Architect

James graduated in architecture from the University of Manitoba in 1956. Further studies followed at MIT. His career, home and family are in Hong Kong, where he designed Asia’s first skyscraper and many of the Orient’s landmark buildings.

His Architectural Portfolio Includes:

1952 – Kino’s Market – Slocan

1961 – Hong Kong Hilton

1967 – American International Assurance

1973 – Jardine House (Hong Kong)

Bali Hyatt Hotel (Indonesia)

1976 – Hong Kong Polytechnic University

1976 – Mandarin Hotel International (Bangkok)

1983 – The Landmark (Hong Kong)

1983 – Jinling Hotel (Nanjing, China)

Jardine House was constructed for the Taipans of the tea, spice and opium trades. An Asian Modernist landmark, it remained the tallest building in Asia through 1980. It is a thin concrete shell like a bamboo with aluminum cladding and some 1700 structurally significant round windows.

“It’s timeless and doesn’t get old fashioned. Keep it classical with elements of good proportion and it will outlive the fashion of the day.” Jardine house design quotation by James Kinoshita

Credits – Research, design and interpretation by Ian Fraser & Associates.